All Our CHIPS on the Table: Is Semiconductor Reshoring Achievable in the U.S.?

Eclipse

|Jun 8, 2023

|6 MIN

Editor’s note: Eclipse Venture Partner Ashwin Pushpala and Partner Aidan Madigan-Curtis highlight three specific areas the U.S. must focus on in order to be successful in reshoring its semiconductor manufacturing capabilities. If you’re focused on building solutions for any of these three areas of need in semiconductor onshoring, we’d love to speak with you.

By: Ashwin Pushpala and Aidan Madigan-Curtis

U.S.-China geopolitical and economic tensions have escalated to historic levels. Yet, the two countries continue to trade at record rates– $690 billion in 2022 alone, including more than a quarter-trillion worth of Chinese imports into the U.S. concentrated primarily in electronics, computers, appliances, and components.

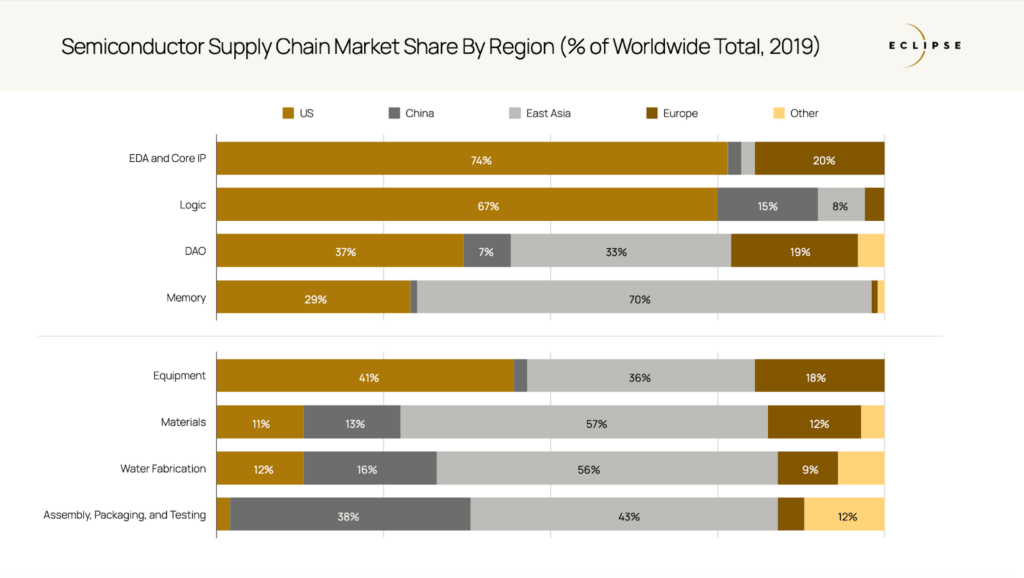

Protectionist rhetoric from Washington — one of the unique topics with bilateral support in the current political zeitgeist — is significantly ahead of the country’s ability to ‘decouple’ from China as a key trading partner. This reality is particularly evident in the semiconductor manufacturing industry, with U.S. companies leading in chip and tooling design, while Asia dominates in manufacturing. In response to the looming techno-economic threat of dependence on Asia for the chips that power everything from our cars to our data centers, the Administration has committed $280 billion over the next decade into domestic semiconductor manufacturing capabilities, including $52 billion targeted at manufacturing and $200 billion for research.

While the CHIPS Act and other recent policies are important steps towards reshoring a critical part of our diminished onshore manufacturing capacity, there are still significant upstream and downstream technology gaps and major hurdles for workforce availability and training that, unless resolved, will significantly stunt the U.S.’ ability to rapidly rebuild a true end-to-end semiconductor manufacturing center.

Eclipse has studied where in the semiconductor supply chain we see the U.S. pulling ahead and where we believe we will be radically behind if joint public and private steps aren’t taken now to cultivate the ecosystems required to foster high-performance semiconductor clusters.

Specifically:

1) Bridging the Skills Gap

A skilled workforce is vital for successful semiconductor onshoring and the U.S. faces a significant shortage – an estimated 50,000 positions this year and 300,000 heads by 2030.

During an event held on May 25th by Bloomberg Intelligence on the strategic semiconductor supply chain, featuring Eclipse Partner Aidan Madigan-Curtis and Intel Corporate VP of Supply Chain Jackie Sturm, Sturm mentioned that she was short “8,000 trade workers,” including electricians, mechanics, steel workers, and construction workers, to build Intel’s Arizona-based fabs at the desired pace, in addition to being “3,000 skilled workers short” to run the operations of the fab once complete.

While the CHIPS Act recognizes the importance of workforce development, it has focused on STEM education and industry partnerships. This is a long-term strategy, not a near-term solution.

Barring any major change to immigration policy, the U.S. will need to solve this gap by attracting new talent to these fields and reskilling/upskilling existing labor supply. And it is not only college-educated engineering talent that is missing in our workforce – some of the most sought-after skill sets in the domestic onshoring effort include construction workers, electricians, tool operators, and industrial mechanics.

Eclipse portfolio company Forge is tackling this challenge. Forge is sourcing, training, and deploying a new industrial workforce, empowering and skilling new trades-workers through a hands-on, job-specific training program designed to rapidly build specialized skills and knowledge, and leveraging modern technology, to deploy talent into the pressing needs of today’s craft labor market.

I believe that too many tech companies see the trades as a problem to be solved — something to automate, gig, and minimize. I founded Forge because I believe that the trades aren't the problem, but the solution. The trades have built the world as we know it and will be what rebuilds it for centuries to come.

While Forge can help satisfy some of the yawning demand for skilled labor, reskilling and redeploying the industrial workforce is a major thesis area in need of rapid innovation.

2) Semiconductor Processing Materials

The semiconductor industry uses a multitude of specialty chemicals, unique materials, and rare gases as part of production methods.

Because of the unique capabilities and processes required to produce such materials, there is an extremely high degree of geographic and supplier concentration with many single points of failure in the system.

Though the U.S. has made some commitments to funding domestic R&D projects for critical minerals production through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the country is almost entirely reliant on imports for its supply of ultra high-purity (UHP) wet chemicals and specialty gases required for foundry operations.

UHP wet chemicals used in semiconductor manufacturing — like sulfuric acid, ammonium hydroxide, and isopropanol — are 100% imported from Asia. And, the demand for UHP wet chemicals is estimated to increase up to 50% over the next five years to support semiconductor reshoring. Ukraine supplies over 90% of the highly-purified neon for chip production in the U.S. These dependencies leave the U.S. extremely vulnerable to supply chain disruptions and geopolitical conflict, as evidenced by the 10x increase in the price of neon following the Russian invasion. Domestic UHP chemical and specialty gas suppliers do not have the capability to completely support the projected demand.

The CHIPS Act has spurred almost $10 billion of announced investments in new facilities or expansions of existing sites that support production of materials required for semiconductor manufacturing. While these investments will help support the initial scale up of foundries in the U.S., semiconductor materials generation processes are quite resource- and capital-intensive. New technologies that reduce reliance on specialty chemicals and gases, or enable cost-effective and sustainable production of these materials, are needed to enable a fully self-sufficient domestic supply chain.

3) Domestic Assembly, Test, and Packaging (ATP) Industry

Wafer fabrication may regain momentum in the U.S., but without a robust Assembly, Test, and Packaging (ATP) industry — also known as “back-end” semiconductor manufacturing — the onshoring ecosystem is incomplete. If our onshore capabilities end at fabrication, we will be left holding nothing but expensive, etched, wafer-sized paperweights, not packaged chips.

As it stands today, most semiconductor products produced at fabs in the U.S. or elsewhere will ultimately need to be sent to Asia, which possesses more than 80% of the world’s ATP capacity.

The CHIPS Act includes provisions that support development of advanced packaging and testing capabilities in the U.S., but specific funding amounts for ATP facilities are not outlined explicitly. Of the >$210 billion in investment committed post-CHIPS Act from companies in semiconductor fabrication, equipment and materials, zero dollars have been committed to reshoring the capital and labor-intensive backend ATP process steps.

75% of chips made today still require simple die attach, wire bonding, and encapsulation techniques that have been used for decades in the industry. Most of the companies with these capabilities have shifted operations to lower labor cost regions in Asia, as these legacy techniques have become commoditized and face significant pricing pressure.

As this shift happened, many ATP companies in Asia already operating with razor-thin margins were forced to innovate to keep up with the miniaturization trends in the front-end manufacturing world. This resulted in advanced packaging technologies like fan-out wafer-level packaging (where redistribution layer traces are routed both inwards and outwards beyond the limits of the die), blurring the line between traditional front-end and back-end foundry processes and increasing value-add for ATP firms that developed these capabilities. Technology leaders like Apple, TSMC, and Intel are all investing heavily in even more advanced packaging methods, such as ‘chiplet’ packaging techniques, enabling a move away from monolithic die design and functional sections of chips to be manufactured separately and integrated ‘on silicon’ as in the front-end world.

However, most other processes in ATP facilities are still done manually and vary significantly between different pieces of equipment. There are no common standards across the ATP industry for carriers, robotics, layout, and facilities design. As a result, most of the operations between equipment are still done manually today. There is significant opportunity in data, logic, control, and materials handling layer automation on top of the existing technologies in the ATP industry to respond to the demands of the front-end fabrication industry.

Conclusion

The global semiconductor market is projected to reach $1 trillion by 2030, presenting a massive economic opportunity.

Unfortunately, the U.S. is insufficiently retooling to reduce our major semiconductor supply chain risks, and might miss the chance to fully capitalize on this rapidly growing market beyond our typical dominance in chip design, unless we can resolve key gaps in the value chain that stretch beyond wafer fabrication.

At Eclipse, we’re focused on partnering with the best founders and teams in the world to tackle these challenges — including labor reskilling, materials fabrication, and next-generation ATP — to invest in the businesses and technologies that will radically shift our capabilities as a country.

Let’s put all of our CHIPS on the table.

If you’re involved in bridging any of the gaps we mentioned in this article, or are more broadly interested in semiconductor supply chain innovation and reshoring, please reach out to us at: aidan@eclipse.vc and ashwin@eclipse.vc.

Follow Eclipse on LinkedIn for the latest on the Industrial Evolution.

Related Articles

Electrifying the Marine Industry: Mitch Lee, Co-Founder and CEO, Arc

Read More